The establishment of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) played a pivotal role during World War II, showcasing the courage and determination of women. This intricate and inspiring history highlights their contributions to Canada’s military efforts, as shared by ottawanka.com.

Early Beginnings: The First Steps

Historically, Canadian women served as nurses during World War I. A significant event occurred in Ottawa in 1918, when discussions were held about establishing an “Auxiliary Corps of the Canadian Women’s Army.” The proposed corps aimed to provide administrative and spiritual support to troops overseas. However, with the war’s end, the project was shelved.

Two decades later, women activists in Victoria revived this vision, forming the British Columbia Women’s Service Corps. This volunteer organization, spearheaded by Joan B. Kennedy, trained women in first aid and other essential skills, though women were still absent from Canada’s official army ranks.

Joan Kennedy and the Volunteer Movement

Joan Kennedy was a patriotic and energetic leader who became the driving force behind creating opportunities for Canadian women to serve their country. Initially an accountant, Kennedy joined the Canadian military, eventually being appointed the commander of the CWAC with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel—a groundbreaking achievement at the time.

Joan Kennedy’s leadership left an enduring legacy, and she retired from the military in 1946.

The War and Unofficial Women’s Corps

With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, unofficial women’s corps sprang up across Canada. These groups, composed of active and patriotic women, included:

- Women’s Volunteer Reserve Corps, operating in Quebec, Ontario, and the Maritime provinces.

- Canadian Auxiliary Territorial Service, active in Ontario and the western provinces.

Volunteers trained in Morse code, map reading, and even infantry drills. For instance, Joan Kennedy’s group practiced in police armouries, while women in Montreal trained in weapon handling under the Black Watch.

Gaining Serious Recognition

Canadian women sought equality with men in military service, striving to be taken seriously. By 1941, they successfully advocated for official women’s auxiliary services in Ottawa.

Joan Kennedy’s efforts were instrumental in this progress. She publicly highlighted the army’s need for women, emphasizing their contributions as clerks, stenographers, and administrative staff. While traditional gender roles initially posed significant barriers, the example of British women in similar roles helped convince Canadian skeptics.

Men questioned how families would function if women joined the army, but women’s contributions to industrialization during World War I eventually changed perceptions.

Contributions of Women in Uniform

By 1941, Canada faced a shortage of able-bodied men, prompting the government to establish the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) on August 13, 1941. Thousands of women joined the effort, filling non-combat roles and freeing male soldiers for the front lines.

Women quickly proved their value, learning skills such as cooking, driving, stenography, telephony, and courier services. Many gained invaluable experience in unofficial paramilitary organizations before joining the CWAC.

Administrative Challenges and Solutions

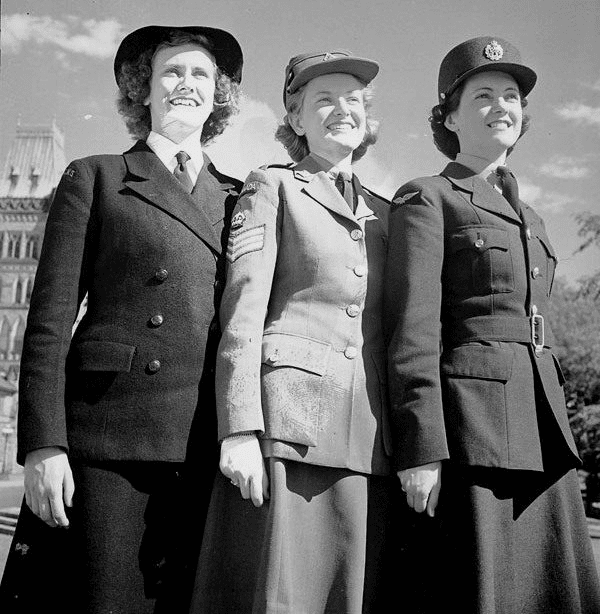

Integrating women into the army raised logistical challenges. On March 13, 1942, the CWAC formally became part of the Canadian Army, addressing many of these issues. Key developments included:

- The badge design, featuring three interconnected maple leaves.

- Collar insignia depicting Athena, the goddess of war, in a helmet.

- The establishment of additional women’s services, including the Women’s Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service.

Ottawa and the National Defence Headquarters

Elizabeth Smellie, a seasoned administrator and former matron of Canadian nursing sisters, became the first officer-administrator at Ottawa’s National Defence Headquarters. She recruited women from patriotic organizations, appointing Joan Kennedy as one of her key deputies.

In the fall of 1942, Kennedy succeeded Smellie, becoming responsible for training female military personnel. She was joined by Margaret Eaton, the daughter of a wealthy Canadian family, who chose national service over a life of privilege.

Why Women Chose Military Service

- Patriotism: Many women felt compelled to serve their country, often transitioning from factory jobs to military roles.

- Adventure: For some, military service offered the chance to travel abroad—a motivating factor for both women and men.

- Skill Development: Free training in areas like cryptography, vehicle maintenance, and signaling attracted many recruits.

To join, women needed excellent health, a minimum height of 152.5 cm, no dependents, and at least an eighth-grade education. Applicants were accepted between the ages of 18 and 45.

A 1943 survey revealed that most women in the military found service enjoyable. They appreciated the camaraderie, opportunities to travel, and the chance to meet people from across Canada. Initially limited to 30 military occupations, women eventually qualified for 55 different roles.

Despite lower pay, women were proud to wear their uniforms, believing that military service positively impacted their outlook and health. Over time, their value in the armed forces silenced skeptics and eased societal tensions.